In 2025, the World Bank quietly released one of its most consequential and unsettling reports in decades — Reboot Development: The Economics of a Livable Planet. At first glance, it looks like another entry in the long parade of sustainability studies. But between its 200-plus pages of tables, charts, and dense economic language lies a simple and radical message: our model of prosperity is collapsing under its own success.

For the first time in the Bank’s modern history, economists openly admit that traditional development metrics — growth, output, and productivity — no longer guarantee human welfare. Instead, they may now undermine it. The report, led by Richard Damania and Esha Zaveri, argues that the global economy has entered a dangerous feedback loop: economic progress damages the biosphere, and biospheric damage erodes economic progress. The two are now locked in a self-defeating cycle.

The backdrop could not be more urgent.

Across the planet, 90% of people live with degraded land, polluted air, or water stress, while in high-income nations, 43% of citizens experience none of these. The uneven geography of environmental harm — from the eroded deltas of Bangladesh to the smog-choked valleys of northern India — mirrors the geography of inequality itself. Environmental collapse is no longer an externality; it’s the new currency of underdevelopment.

In one sense, Reboot Development is a macroeconomic obituary for the 20th century’s growth paradigm. But it’s also a pragmatic blueprint for the next phase of human civilization — one that redefines progress as stability within planetary boundaries. It replaces the question “How much can we grow?” with a far more consequential one: “How long can we live well?”

The numbers in the report are arresting. Forests that once cooled the planet now vanish at a rate that erodes $379 billion in rainfall-driven productivity each year. Nitrogen fertilizer — the backbone of industrial agriculture — inflicts $3.4 trillion in global damages annually. Air pollution alone kills 5.7 million people per year, quietly outpacing war, hunger, and tobacco as a leading global cause of death.

And yet, amidst this grim arithmetic, the report carries a cautious optimism. It highlights China’s air-quality turnaround, India’s renewable energy surge, and Latin America’s new conservation economies as signs that decoupling growth from environmental degradation is possible. The challenge now is scale, coordination, and willpower.

Table of Contents

Rebooting Development: The New Economics of Survival

There’s a growing consensus that development itself is in crisis. The World Bank’s 2025 flagship report “Reboot Development: The Economics of a Livable Planet” delivers an unmistakable verdict: humanity’s prosperity, once powered by industrial expansion and agricultural intensification, has begun to cannibalize the very systems that sustain it.

In a line that could define the century, the authors write that “development cannot succeed on a damaged planet.” The numbers that follow read like a planetary audit — grim, data-backed, and unavoidable.

The Numbers That Shock the Planet

The report’s first finding is staggering:

“Around 90% of people globally live with degraded land, polluted air, or water stress.”

In low-income countries, the statistic worsens —

Nearly 80% of residents face all three environmental stressors simultaneously. In high-income nations, by contrast, 43% of citizens experience none.

This is not just an environmental divide; it’s an economic one. The burden of environmental degradation maps neatly onto poverty itself. Reboot Development’s global charts (Figure MM.1–MM.6) draw a portrait of inequality written in air, water, and soil.

Planetary Biomass Breakdown

Perhaps the most haunting figure comes early in the report:

“Humans and their livestock account for 95% of the Earth’s mammalian biomass.” Wild mammals — elephants, tigers, whales, even the microscopic plankton that sustain marine life — now constitute a mere 5% of total mammalian weight.

A century and a half ago, that ratio was 50–50. The transformation marks, in quantitative terms, the Anthropocene’s economic footprint — the era when human production outweighed natural life.

From Abundance to Breakdown: Humanity’s Economic Dilemma

The World Bank economists frame the crisis not as an environmentalist plea but as a macroeconomic emergency. The report argues that unsustainable production — once a hidden cost of industrial growth — has reached the point of diminishing global GDP returns.

The data supports the claim. Each year:

- $379 billion is lost from agricultural productivity due to deforestation-driven rainfall decline.

- $3.4 trillion is the estimated annual global cost of nitrogen pollution — the byproduct of fertilizer excess.

- 5.7 million people die prematurely from outdoor air pollution — exceeding global deaths from tobacco, malnutrition, and armed conflict combined.

The macroeconomic ripple effects are massive. The report calculates that polluted air not only kills but reduces labor productivity, weakens cognitive performance, and lowers regional GDP growth — particularly in South and East Asia, where industrialization continues to accelerate.

“The scale of human impacts has turned the biosphere from a passive backdrop into an active casualty of growth,” the authors conclude.

The Economics of Water, Air, and Soil: Quantifying Collapse

Forests as Rainmakers

Forests are often celebrated for carbon capture — but Reboot Development highlights a different, rarely quantified role: water production. Nearly half of all global rainfall originates from vegetation, primarily forests.

When those forests are lost, rain literally vanishes. The report estimates:

Deforestation-induced rainfall loss costs Amazonian economies $14 billion annually in reduced agricultural and hydrological productivity.

Globally, the drying of soils and moisture decline costs 8% of agricultural GDP, or approximately $379 billion per year. Natural forests — not plantations — play the key buffering role, reducing drought-driven GDP losses by over 50%.

The Nitrogen Paradox

Few substances capture humanity’s double-edged mastery of nature like nitrogen fertilizer. It doubled food yields during the 20th century, helping feed billions. Yet, the World Bank report reveals, half of the world’s food is now grown where nitrogen use does more harm than good.

Instead of boosting productivity, excessive nitrogen degrades soil, contaminates water, and produces atmospheric pollutants like nitrous oxide — a greenhouse gas 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

“Excess nitrogen pollutes land, air, and water — costing up to $3.4 trillion annually worldwide,” the report notes.

The challenge, economists say, is not to abandon nitrogen but to rebalance its economic efficiency — through smarter subsidy designs, regenerative agriculture, and precise soil monitoring.

Air: The Deadliest Invisible Commodity

Air, once free and infinite, has become the most lethal public good.

According to the report, 5.7 million deaths per year are linked to outdoor air pollution — making it “the deadliest risk no one sees.”

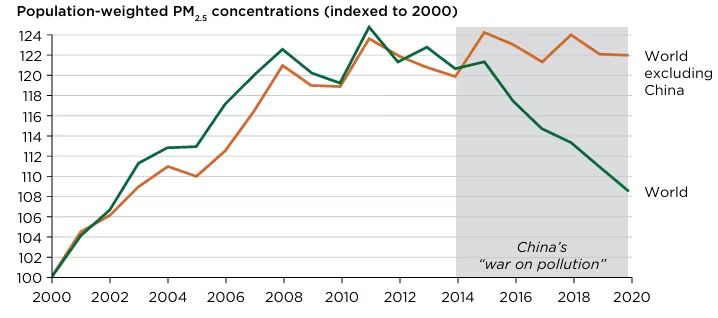

But there’s hope in the data. China’s so-called “war on pollution” between 2013 and 2023 succeeded in reducing PM2.5 concentrations by over 40%, while maintaining GDP growth. The result:

A global “bend in the pollution curve” driven largely by a single country’s policy transformation.

The World Bank cites this as proof that decoupling growth from environmental damage is not only possible but already underway.

Across all countries, efficiency improvements between 2000 and 2020 have:

- Reduced water use by 50%

- Reduced land use by 69%

- Reduced air pollution (PM2.5) by 59%

Still, the report warns that efficiency alone cannot save the planet — the economy must evolve to “produce better things,” not merely “produce things better.”

Jobs, Growth, and Greenbacks

At the heart of the report lies a paradox: the environmental crisis is also a labor crisis.

Agriculture and fisheries — the sectors most dependent on natural capital — support 3.2 billion people worldwide. Pollution, soil degradation, and extreme weather now directly threaten those livelihoods.

When the land fails, jobs vanish.

But Reboot Development finds that less-polluting sectors generate more jobs per dollar invested.

“On average, green sectors create twice as many jobs as polluting industries,” it states — 9 jobs versus 3 jobs per investment unit for men, and 14 versus 6 for women.

This pattern reframes the old “growth vs. environment” debate. In practice, clean growth is more labor-intensive, equitable, and socially beneficial. It turns out that greenbacks grow greener when pollution declines.

Transition Minerals: The Bedrock and the Trap

A new industrial scramble is unfolding beneath our feet. The World Bank warns that demand for transition minerals — lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare earths — will quadruple by 2040 as countries race to electrify their economies.

Yet this “green gold rush” is repeating old mistakes:

- Deforestation rates are higher around transition mineral sites than around traditional mines.

- Many deposits overlap with biodiversity hotspots, Indigenous lands, and water-scarce regions.

“Significant reserves exist in high-income countries, while the ecological risks concentrate in low-income ones,” the report notes.

The authors call for stronger governance, local value chains, and transparent supply systems to prevent a new era of resource colonialism — a warning echoed by environmental economists since the 1970s.

Fixing the System, Not the Symptom

The final chapter of Reboot Development reads like a manifesto for global policy reform. It calls for a three-pronged approach to sustainability that can be summarized as:

Inform. Enable. Evaluate.

- Inform: Data transparency is the new oil. Real-time satellite monitoring, public pollution indices, and digital land registries can democratize accountability.

- Enable: Policies must be integrated — connecting agriculture, water, and trade. A fragmented approach often backfires, like subsidizing fertilizer while fighting algae blooms.

- Evaluate: Environmental policy should behave like venture capital — test, measure, and scale what works.

In a particularly striking aside, the report references “The Thirsty Cloud” — noting that artificial intelligence data centers now consume massive water volumes for cooling, turning digital growth into a physical environmental cost. It’s a symbolic twist: even our virtual progress drains real rivers.

Beyond GDP: The Reboot Ethos

Behind the World Bank’s dry tables lies a profound philosophical shift. The report effectively concedes that economic success can no longer be measured by growth alone.

Instead, it proposes a new kind of “livability index” grounded in biosphere stability and natural capital integrity.

The numbers underscore the stakes:

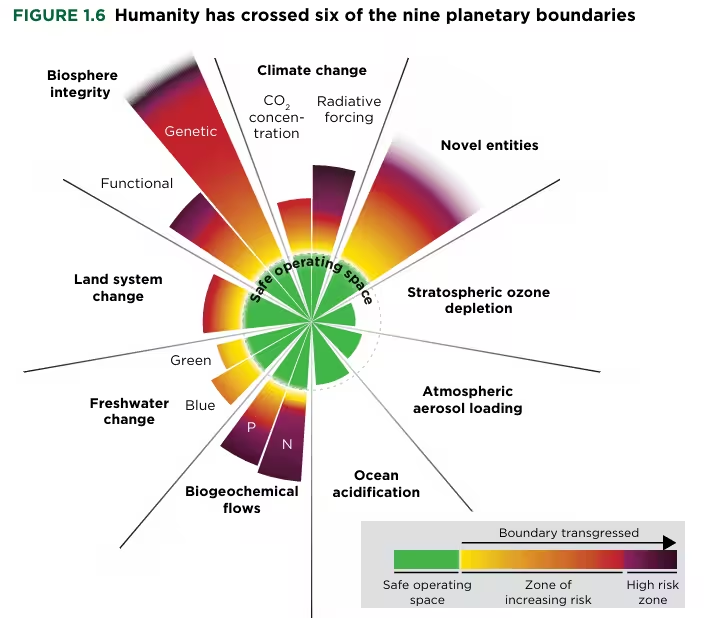

- Six of nine planetary boundaries have already been breached — including freshwater, land, nitrogen, biodiversity, climate, and chemical pollution.

- 92% of the global population lives under at least one environmental stressor.

- The biomass of human-made materials now outweighs all living organisms.

As the report’s lead economist Richard Damania puts it, “We’ve stopped living on Earth and started living off it.”

The solution, he suggests, isn’t about retreating from growth — it’s about redesigning growth as stewardship.

Toward a Livable Planet Economy

If the report’s tone feels urgent, it’s because the economics are clear.

Environmental degradation is now a macroeconomic variable — one that dictates productivity, stability, and even peace.

The question for policymakers, investors, and citizens alike is not whether the planet can afford sustainability, but whether the economy can afford collapse.

The authors close with a challenge:

“Countries that build industries thriving within ecological limits will be the ones that prosper into the future.”

In other words, development must reboot — not merely in code or in policy, but in worldview.

Bangladesh in The Economics of a Livable Planet

The report highlights Bangladesh in several contexts, underscoring both its vulnerabilities and innovative responses to climate and environmental challenges:

- Poverty and Environmental Stressors: Bangladesh is identified among the top 10 countries where poverty overlaps with exposure to environmental risks such as unsafe water, poor air quality, and land degradation.

- Agricultural Innovation: The country is cited as a successful case in improving fertilizer efficiency. Training farmers to use a simple leaf color chart reduced fertilizer use by 8% without lowering yields, saving 180,000 tonnes of nitrogen fertilizer valued at around $80 million (14% of the national input subsidy budget).

- Digital Divide and Climate Vulnerability: Bangladesh appears in a figure linking internet access to climate resilience. The data show that despite being highly exposed to climate hazards, internet penetration remains limited, which constrains adaptive capacity.

- Social Protection and Climate Shocks: Anticipatory cash transfers in flood-prone regions of Bangladesh reduced food insecurity by 36% while protecting assets and improving child nutrition. This is cited as a global example of how social protection systems can buffer climate impacts.

In summary: The report portrays Bangladesh as a climate-vulnerable country that nevertheless demonstrates leadership in adaptive policies—especially in fertilizer efficiency, social protection, and anticipatory disaster response.

Read also: Thailand’s Sex Tourism